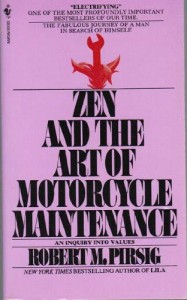

This novel captivated me in my early 20s. The mystical philosophy of ‘goodness’ Pirsig explores fascinates me. It’s not a perfect book, though. And over the years I discovered numerous faults. For example, Pirsig idealises — romanticises — motorcylce travel.

On a cycle the frame is gone. You’re completely in contact with it all. You’re in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming. That concrete whizzing by five inches below your foot is the real thing, the same stuff you walk on, it’s right there, so blurred you can’t focus on it, yet you can put your foot down and touch it anytime, and the whole thing, the whole experience, is never removed from immediate consciousness.

Well, to be completely in contact with it all, try a bicycle…or walking. But that’s not the point I really want to make.

Being in a scene is different from being present in a scene, something Pirsig himself should have recognised just eight pages later when, caught up in all his philosophical ponderings, he misses an exit on the highway he’s travelling.

Chris asks, “What are we stopping for?”

“I think we missed our turn back there,” John says.

I look back and see nothing. “I didn’t see any sign,” I say.

John shakes his head. “Big as a barn door.”

“Really?”

He and Sylvia both nod.

[…]

And now tagging along behind them I think, Why should I do a thing like that? I hardly noticed the freeway. And just now I forgot to tell them about the storm. Things are getting a little unsettling.

With these two passages in my mind, I wrote the following travelogue entry while holed up for the night in a cheap Death Valley motel.

The world reels by, unfurling at 90 miles an hour. At this speed, travel gains the sense of dance even on a relatively straight, flat interstate such as this section of I-395. I am aware of the countryside, the gentle undulations of the valley floor contrasting the angular gyrations of slowly eroding hillsides; I am aware of the thinning stands of Joshua Tree and can pick out a few individual shapes for their magnificence or their decrepitude; I notice the snowline band so evenly frosting the hill tops, that I am climbing toward the line, that I am now above it and that the snow along the roadside proceeds from spare dollops to a thin crust with mesquite poking through.

If I slowed down–if I left the interstate and slowed down–if I were off the interstate riding a motorcycle, or better yet a bicycle–if I were walking along some nearly forgotten footpath, the world would appear different. Some have written the difference is qualitative, that we see the world from an inherently better perspective when we slow down, when we stop to smell the roses, when we choose a more interactive mode of transportation. I have been one of those writers. But it occurs to me now that I am painting the broad strokes of the desert in my mind, like the underlying wash that begins a watercolor landscape.

I have hiked through the high desert and driven through it on interstates, state roads, back roads and dirt tracks. I have flown over it dozens of times. At 36,000 feet you see patterns that are impossible to imagine from the ground, no matter the rate of speed. Seated by the window on one such flight, the desert sliding below, I recalled from a hiking trip the sparsely vegetated, rock-strewn sand stretching mile upon mile between ragged stone walls. The merest trickle of water ate the earth. I then understood how the drainage sparse desert rainfall could carve such a fantastic geometry from rock.

Northbound on I-395 I am overtaken by an F-15 airforce jet. Passing on the right just one hundred feet overhead, it hugs the valley floor, banks dramatically once and disappears over the next rise. I am crawling northbound on I-395, nearly stopped at 90 miles an hour. I look again at the pointilistic patches of snow, at the pipe-cleaner arms of the Joshua Trees. It is so much easier to appreciate the fine details of the desert when one takes their time.

The speedometer shows numbers all the way up to 120mph, which sets me to wondering if a Plymouth Neon with a four cylinder engine can really go that fast.

It can.

And what is not good —

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?